(Bloomberg) — Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers warned of a testing period for the U.S. economy in coming years, with the risk of recession followed by stagnation.

In an interview with the Bloomberg Economics “Stephanomics” podcast, Summers said that the Federal Reserve had been late to spot the dangers of inflation and that delayed action to cool prices could potentially tip the economy into a slump.

“If I thought we could sustainably run the economy in a red-hot way, that would be a wonderful thing, but the consequence — and this is the excruciating lesson we learned in the 1970s — of an overheating economy is not merely elevated inflation, but constantly rising inflation,” Summers said. “That’s why my fear is that we are already reaching a point where it will be challenging to reduce inflation without giving rise to recession.”

Summers, a paid contributor to Bloomberg and a professor at Harvard University, spent much of 2021 arguing that the Fed, Biden administration and investors were all underestimating the risk of a pandemic-fueled acceleration in inflation. He has repeatedly said that putting off tackling the challenge would then require a bigger crackdown on demand to quash the surge in prices.

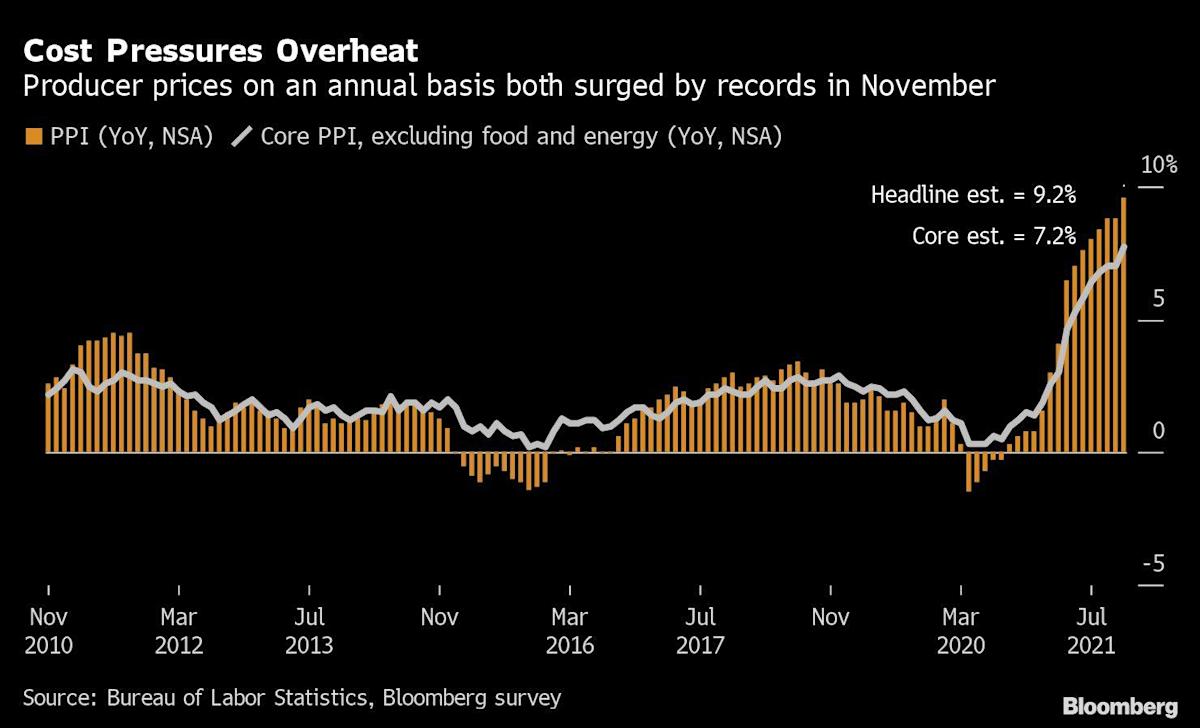

The biggest leap in the consumer price index since Ronald Reagan was president has forced many to shift closer to Summers’s view. The Fed this month pivoted towards tightening monetary policy next year more aggressively than it had anticipated as recently as September.

“We’ve got a fairly serious inflationary situation,” said Summers.

Even so, he said the central bank was still too confident in projecting sustained low unemployment alongside receding inflation. The central estimate of Fed officials this month was for a 3.5% jobless rate in each of the next three years.

“It doesn’t seem to me that it is the most intuitive reading of our macroeconomic history,” Summers said.

Price pressures mean borrowing costs in financial markets may have room to rise — although investors seem to be betting that growth and inflation will ultimately be reined in, said Summers.

Fed officials this month forecast their target for the overnight policy rate jumping from zero currently to 1.60% at the end of 2023 and to 2.10% in 2024. But traders see it differently, with eurodollar futures contracts pricing in about 1.50% short-term rates on both dates. At the other end of the yield curve, rates on 10-year Treasuries are currently below 1.50%.

“I’m surprised by how low long-term interest rates are,” said Summers. “Markets are foreseeing that we will do what’s necessary to contain inflation — and that process will be quite contractionary.”

Summers also doubted whether “running the economy hot on an unlimited basis” would be enough to force up the wages of workers as some have argued, warning instead that rising inflation would eat into households’ paychecks.

“There are no examples of successful inflationary policy that has worked out to the benefit of workers,” he said, citing historical efforts in the U.K. and U.S. in the 1970s, along with similar campaigns in Latin America. “It backfired with respect to the very people it was trying to help.”

As for the longer term, Summers said the risk remained of “secular stagnation,” a Depression-era situation in which trend economic growth rates are reduced and interest rates are lower than historic norms. He first started warning of such a mix in 2013.

“Secular stagnations are a real risk looking out a few years,” he said.

“I’m really not sure what’s going to come after this current episode,” he said. “I’m certainly not confident that we’re going to have sustained excess demand for many years. The challenge is that we’ve pumped up aggregate demand now, and then who knows how we’re going to work our way through back to more levels of demand.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.