The Federal Reserve building is seen in Washington, U.S., January 26, 2022. REUTERS/Joshua Roberts/File Photo

Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.com

Register

Feb 24 (Reuters) – U.S. Federal Reserve officials on Thursday began taking stock of how the unfolding conflict in Ukraine might influence the economy and their planned shift to tighter monetary policy, with investors and some officials suggesting it could slow but likely not stop a planned round of interest rate increases.

Oil and commodity price shocks and a possible blow to global growth and confidence were clear risks, analysts said, and one Fed policymaker said the events of the last 24 hours could weigh on upcoming Fed decisions.

“The implications of the unfolding situation in Ukraine for the medium-run economic outlook in the U.S. will also be a consideration in determining the appropriate pace” for raising interest rates, said Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester.

Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.com

Register

Richmond Fed President Thomas Barkin said the case for U.S. rate increases remained “robust,” but also called the invasion an “unsettling” event that would force policymakers to think through what might happen.

The risks could be as obvious as high oil prices weighing on consumer spending and raising inflation even further, or as unknowable as how Russia might respond to U.S. sanctions.

“Underlying demand is strong. The labor market is tight. Inflation is high and broadening,” Barkin said, describing the basic case for rate increases. “But I will say that it is unsettling to hear the news. As always happens you have to start and think through where could this thing go that you might not have forecast originally.”

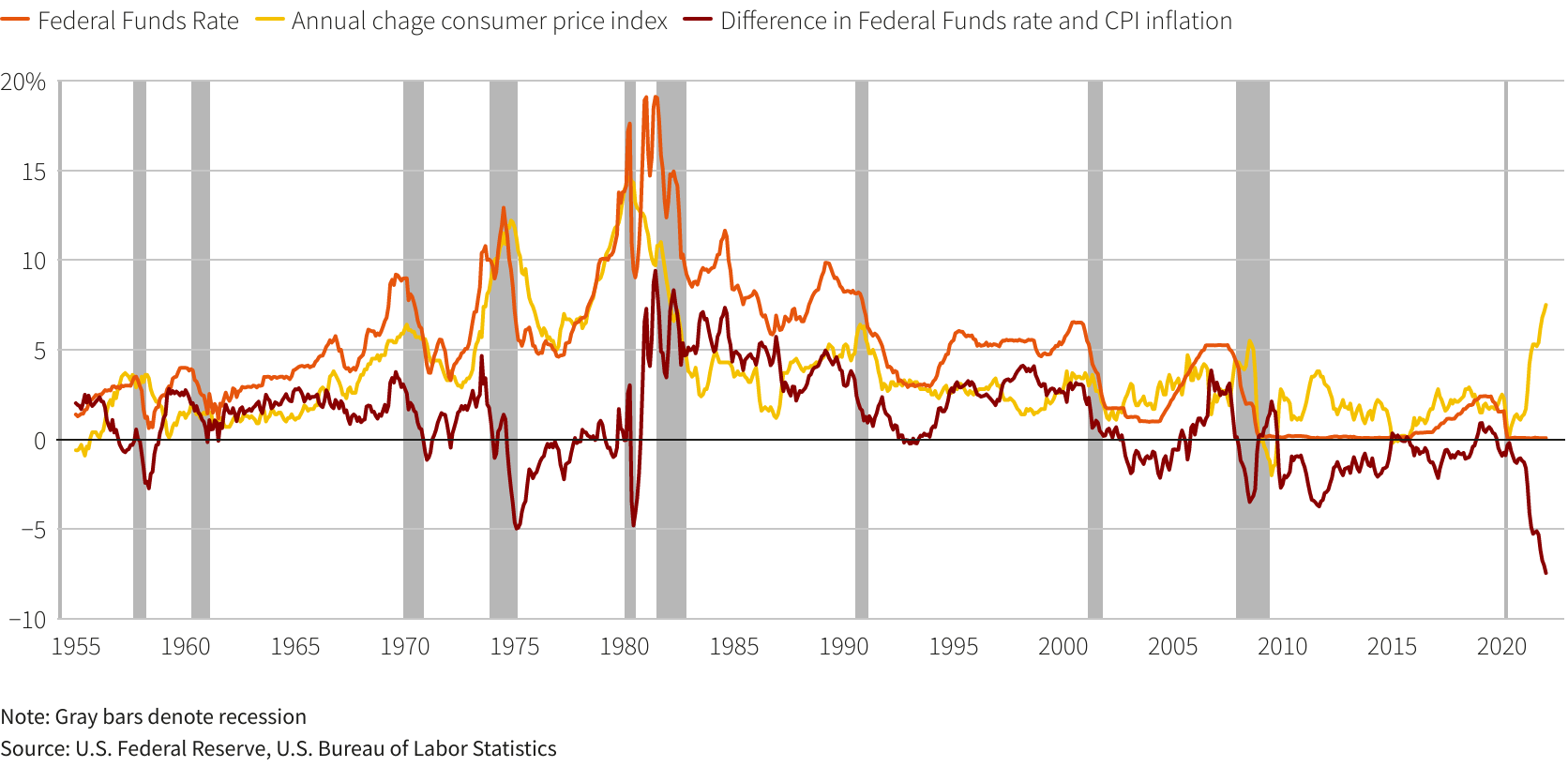

The Fed plans to raise interest rates beginning in March as it battles inflation that has hit multi-decade highs.

Fed policy has already been complicated by the unpredictable impact of a once-in-a-century pandemic, and must nowaccount for a likely energy price shock and other uncertainty following Russia’s military move into Ukraine. read more

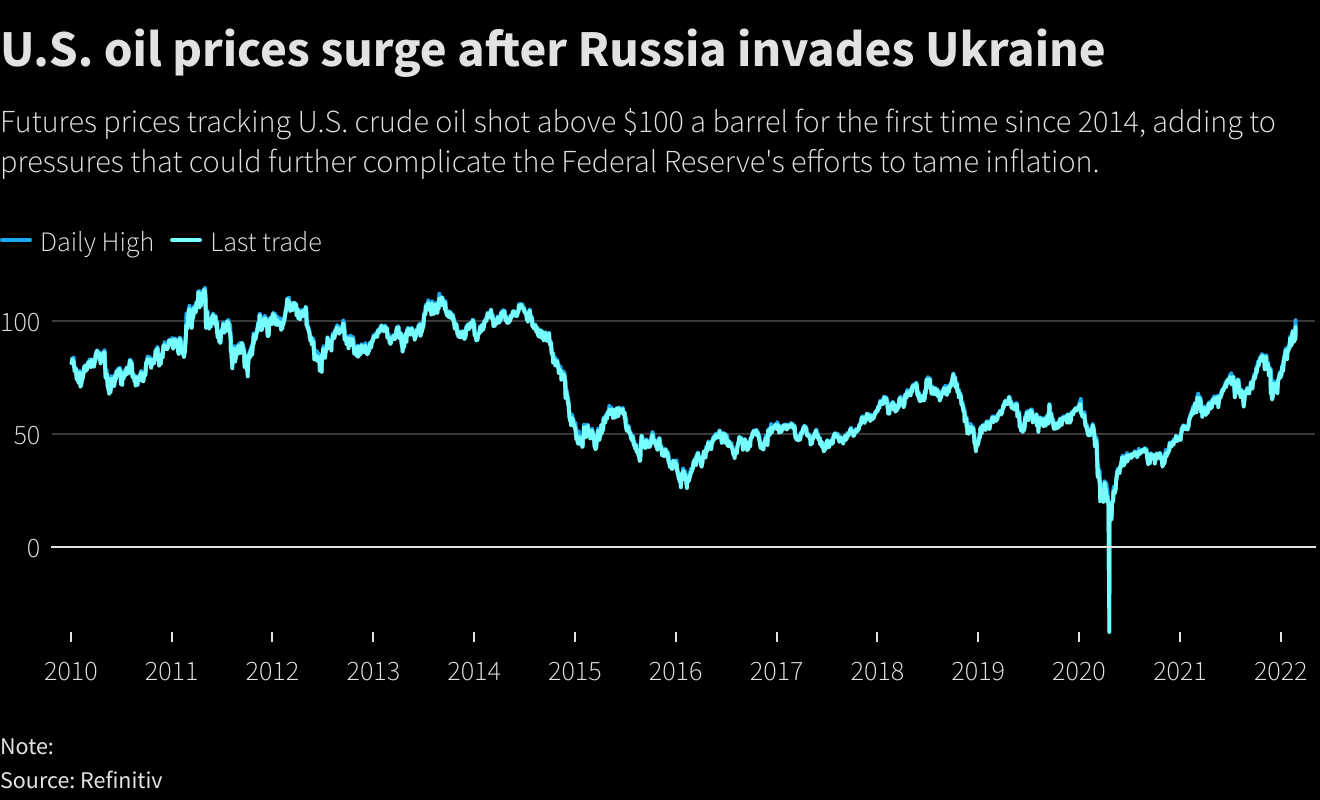

Oil prices spiked overnight, with U.S. crude oil futures topping $100 a barrel for the first time since 2014, and stock prices slid by more than 1% in midday U.S. trading. [nL4N2UZ4CT]

Investors have now all but ruled out a larger half-percentage-point rate increase at the Fed’s March meeting. CME Group’s widely followed FedWatch tool was signaling at one point that the probability of a hike that large had fallen overnight from about 33% to less than 10%. A quarter-point increase is still anticipated as the Fed begins to lift its target policy rate from the near zero level set at the outset of the pandemic.

STAGFLATION RISK

But the events overnight have dealt the central bank an unexpected new dynamic, an echo of the oil price shocks of the 1970s that were also driven by geopolitical conflict. In that case it was war and other tension in the Middle East, and came at a time when the U.S. economy was far more dependent on imported energy, and U.S. industry far less energy efficient.

Still, Fed officials were beginning to think through the implications of an event that had the potential to both slow growth and add to inflation.

“We’ll be watching this closely here in Atlanta and across the Federal Reserve system to assess the economic and financial impacts,” Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic said during a virtual event. Still, he said the Fed’s first-order problem now is controlling inflation, and that he is ready to raise rates by as many as four quarter-point increments this year, “and depending on how things go it may be more than that.”

A few hours before the invasion was reported, San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said that with U.S. inflation as high as it is and the labor market strong, the Fed should go ahead with rate hikes even with the uncertainty of a Ukraine-Russia conflict. “I really don’t see, unless things get materially worse…that this is going to have an effect” on the Fed’s decision to start raising rates in March, she said at an event Wednesday in Los Angeles. read more

But officials may now tread a touch more carefully until the breadth of Russia’s actions, and how they affect oil prices, financial markets, and the broader economy, become clearer.

“We think probably now we have reached a tipping point where this is a situation that could start to have impacts on confidence…we know that it’s affecting financial markets,” said Jennifer McKeown, Head of Global Economics Service at Capital Economics.

It is unlikely to derail tightening plans, but “central banks are probably more likely now to be starting to err on the side of caution and worry about the adverse effects on their economy.”

The immediate economic risk appears larger for Europe than the United States, with European Central Bank policymakers convening Thursday in a previously scheduled “informal” gathering that may become a crisis meeting. read more

Still, the crisis threatens to delay the resolution of prominent factors that have fanned U.S. inflation higher such as global supply bottlenecks, which could keep price pressures high while denting growth prospects.

Beyond the very near term, “the impact of the stagflationary shock is ambiguous and could be net hawkish,” Evercore ISI analysts wrote. “Both the adverse sides of the macro distribution move up: the right tail risk of continued excess inflation in the medium term and the left tail risk that efforts to curb this inflation…end up causing a recession.”

“In the context of the sizeable disruptions to supply chains and energy prices already, this will…complicate the policy response of central banks,” wrote analysts with TD Securities. “The Fed and the U.S. may be removed enough to keep to hiking as planned, though risks shift in terms of 25 (basis point) increments rather than anything more aggressive.”

Register now for FREE unlimited access to Reuters.com

Register

Reporting by Howard Schneider and Jonnelle Marte; Additional reporting by Lindsay Dunsmuir and Ann Saphir;

Editing by Dan Burns and Andrea Ricci

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.