Powell should pay attention here so he’s better prepared at the next press conference when asked about the impact of inflation on regular Americans.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

Fed chair Jerome Powell’s reaction today after he saw the consequences of his reckless monetary policies. Imagined by cartoonist Marco Ricolli for WOLF STREET.

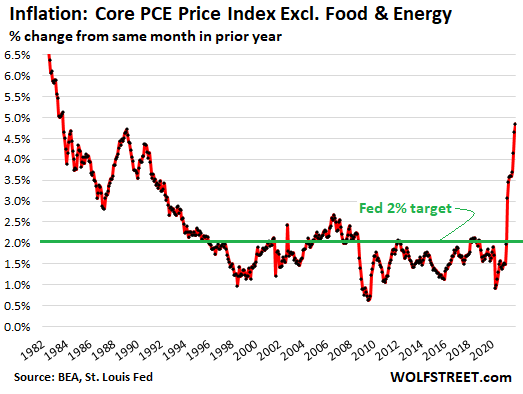

The “core PCE” price index, which excludes food and energy and which understates inflation by the most of all of the government’s inflation measures and which is therefore wisely used by the Fed for its inflation target, spiked by 0.50% in December from November, and by 4.9% year-over-year, the worst inflation reading since 1983, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis today. As measured by this lowest lowball inflation measure, inflation, is well over double the Fed’s inflation target:

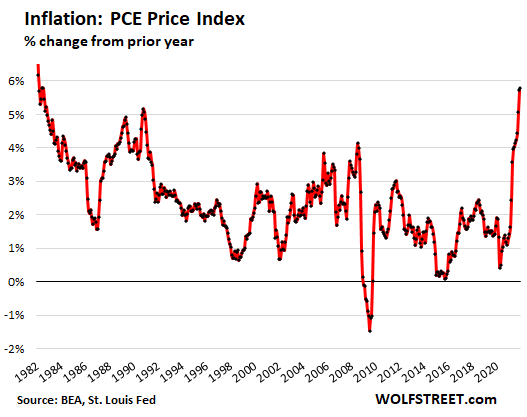

The overall PCE inflation index, which includes food and energy, spiked by 0.45% in December from November, and by 5.8% year-over-year, the worst reading since 1982.

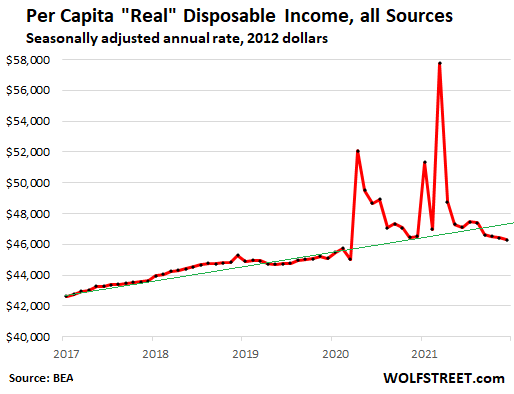

So how did this inflation – the worst in 40 years – impact wages and salaries? Powell should pay attention here so that he is better prepared for the next post-meeting press conference when some wayward reporter asks him about the impact of inflation on regular Americans.

Adjusted for inflation, per-capita disposable income (income from all sources minus income-related taxes, on a per person basis) fell by 0.3% for the month and fell by 0.5% year-over-year, continuing the relentless decline that started last summer when inflation took off at a velocity not seen in decades. Note the pre-pandemic, pre-massive-inflation trend line (green):

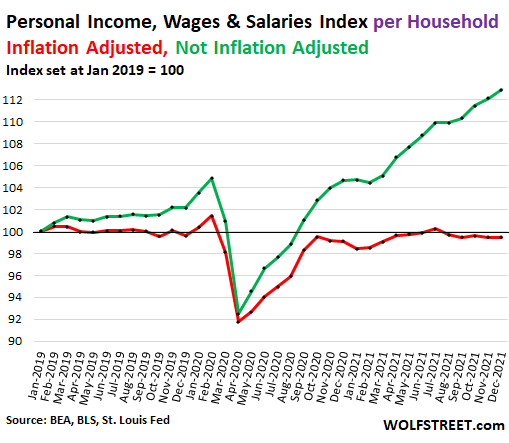

Compensation from wages and salaries, not adjusted for inflation, and not including government transfer payments, rose by 0.7% in December, by 9.2% year-over-year. And those kinds of wage and salary gains would be something to celebrate. But they were eaten up entirely by inflation. On a per-household basis, after inflation, those wage and salary gains disappeared entirely, opening up an ever-wider gap between the money people earn with their labor, and what’s left over after inflation.

As inflation whittled down the purchasing power of labor, the rising number of households reduced the slice each household gets of the aggregate inflation-diminished income figures to where inflation-adjusted income from wages and salaries is now below where it was two years ago and below where it was three years ago:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()