Wages Surged, But Raging Inflation Crushed the Purchasing Power of those Wages.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

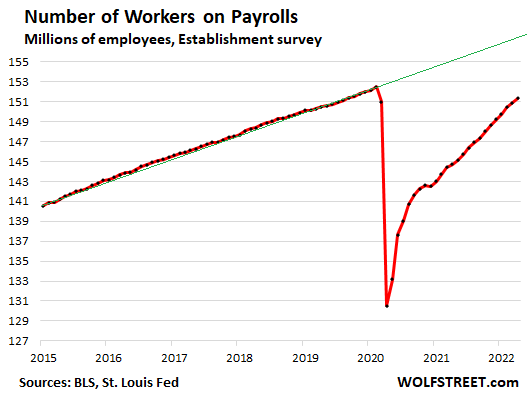

Employers added 428,000 workers to their payrolls in April, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics today, bringing the total number of employees to 151.3 million. Over the past three months, employers added 1.57 million employees.

But the number of employees remains far below pre-pandemic trend (green line), and remains below the peak just before the pandemic:

Employers of all kinds have been lamenting the difficulty in hiring people. They have raised wages in order to hire and retain people, and there is now enormous churn, with employers luring workers from other employers. But they’re not able to draw enough new or sidelined workers into the labor force, and these “labor shortages” continue to constrain hiring.

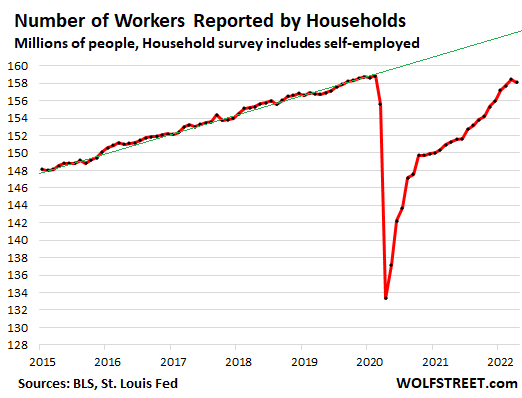

Households reported that the number of working people — including the self-employed, gig workers, and entrepreneurs that are not included in the Employer data above — declined by 353,000 in April, but over the past three months jumped by 931,000, bringing the total to 157.7 million workers.

That dip in April is reminiscent of the occasional month-to-month dips before the pandemic, such as in September 2015, October 2017, and August 2018 that, with hindsight, weren’t a change in trend but month-to-month noise.

The labor force and “labor shortages.”

The jobs report released today is based on two massive groups of surveys: one survey goes to employers; and the other goes to households. They each give a different view of the labor market, one from the employer’s side, and the other from the household’s side. The labor force, the number of unemployed people, the unemployment rate, etc. are based on the household survey.

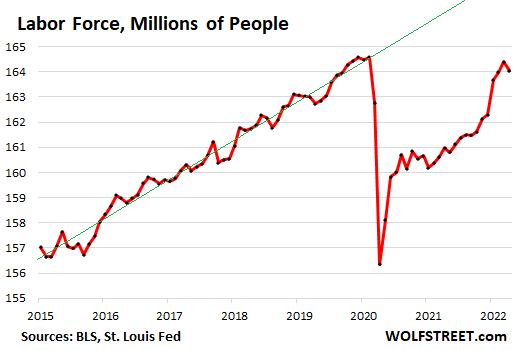

The labor force – the people who are working plus the people who are looking for work – dipped in April, by 363,000 people, similar to the dips and pops before the pandemic along the trend line.

At 164.0 million people, the labor force was still far below pre-pandemic trend (green line) and 537,000 workers below the peak just before the pandemic:

The far-below-trend labor force is another manifestation of the “labor shortage.” It shows that there are lots of people in the US that could work but are not in the labor force for whatever reason.

Among the reasons for the below-trend labor force are ongoing health concerns, difficulties of finding affordable daycare, a well-documented above-normal wave of retirements, people not working because they made a lot of money from stocks, cryptos, and real estate over the past few years (now dwindling), and people not working because they’ve decided to day-trade their way into a fulfilled life. There was some of that during the dotcom bubble, and part of it reversed during the dotcom bust. So let’s see.

The “labor shortage” is also documented by separate data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics by the spike in job openings that reached a record of 11.5 million in March, up by 36% from a year ago, and up by 57% from the same month in 2019. There were 4.2 million more job openings this March than before the pandemic! Employers have all hammered home the same point: It has become very difficult to fill open positions.

Wages surged, but raging inflation far outran them.

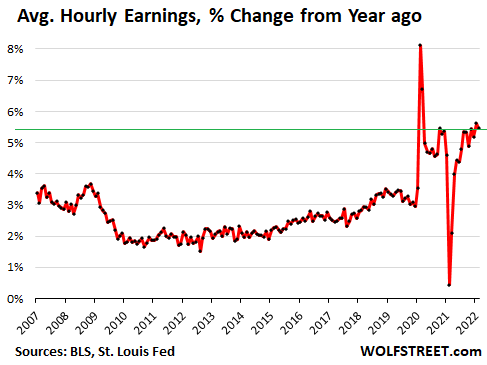

Overall average hourly earnings rose to $31.85 in April, up by 5.5% from a year ago. Beyond the distortions during the pandemic, April along with March were the largest year-over-year increases in the data that goes back to 2006. This category includes supervisors and management, along with employees of all kinds in all industries:

The distortions during the pandemic occurred when millions of low-wage workers were laid off while office workers switched to working from home, which took millions of lower-paid workers out of the average hourly earnings, thereby inflating the average hourly earnings. And when they returned to work, their lower pay reduced the average back into the range.

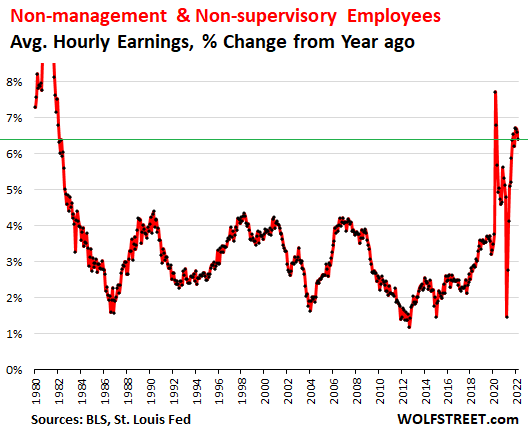

Average hourly earnings of non-management workers, the “production and nonsupervisory employees,” is a data set that goes back many decades and comprises workers in all industries of the private sector, and in all jobs that are non-management jobs, ranging from waiters to Google coders.

For these non-management workers, the average hourly earnings rose to a record $27.12, up by 6.4% from a year ago. Other than the lockdown distortions in the spring of 2020, the past five months were the biggest year-over-year jumps since early 1982. This confirms other reports that percentage wage gains – not dollar wage gains!! – have been strongest at the lower end of the wage spectrum.

Raging inflation and the labor force?

These big wage gains were not enough to keep up with inflation. The headline Consumer Price Index (CPI-U), the measure most commonly cited, jumped to 8.5%.

The less-often cited Consumer Price Index for All Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), which is used for the Social Security COLAs, jumped to 9.4%.

So with average wage gains in the 5.5% to 6.4% range, the purchasing power of those surging wages got crushed by raging inflation.

Raging inflation is the enemy of the people who work. For workers, there is nothing good about inflation. They’re at the losing end of this deal. There are beneficiaries of inflation, including companies that can raise their prices to whatever, and heavily indebted entities with fixed-rate debts, but it’s not workers. They’re getting hammered by this inflation.

This raging inflation might thereby in part explain the peculiar phenomenon why the big wage increases have not been big enough to draw people back into the labor force: Effectively lower “real” wages don’t provide enough incentive to rejoin the rat race.

Much bigger wage increases might then be assumed to cure the labor shortages. But much higher wages would fuel the wage-price spiral further, and wages would never be able to outrun it, and “real” wages would continue to decline, which would then effectively not provide any incentives to rejoin the labor force, and would not improve the labor shortages.

The other option is to crack down on inflation, which would allow wage gains to catch up with price gains and maybe make it worthwhile again to join the rat race. That’s what the Fed is trying to do now, even if too little too late. And the Fed has been citing the labor market as one of the reasons for its crackdown on inflation.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()